Clover Wetherly

Clover

a country mouse

|

|

|

She’s one of two ragged companions tracking down the canyoned road, a pack chocobo tethered to their lonely caravan. At night they find themselves sheltered between walls, warm their numbed hands around a campfire burning gorse wood and rushes. They share watering holes with heavy-headed buffalo, under the black beady eye of lizards laid out flatwise against the rocks. They crawl underneath lone trees in the desert while the day burns.

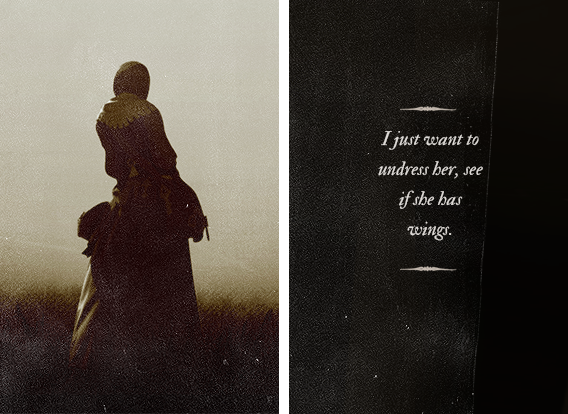

The girl has the soft grey pelts of rabbits slung over her shoulder; she’ll sell them the next market town. Now she’s traded her peasant’s wooden clogs for boots; her skirt is hitched up to her belt to reveal a flimsy, mudstained petticoat. By the narrow waist of her bodice is strapped a skinning knife.

She’s a drifter and a trapper and she dresses the pelts of hares where they catch them, by the road, in the scant, thirsty woods. From her poacher father she’s inherited a hard stomach; from an early life lived in dreams she’s inherited a soft heart.

The sun pricks holes in the weave of her hat as the day reaches its bleached zenith, and Clover smiles while her companion glowers; they continue upon the road to Ul’dah.

themes

The Fool - She knows little of the world beyond the hedgerows of the farm she abandoned. Her world is painted in the simple and crude pictures painted on diviner’s cards, motley and gaudy and colourful. But watch: she’s resilient as a daisy, and not easily crushed underfoot.

Yellow Jackets, Black Hearts - ‘Brand a man a thief, and he’ll never find himself a day’s worth of honest labour again.’ No hardened criminal, she, yet the farmgirl nurses in her breast a suspicion towards all those who bear arms in service of the law, from the time she saw her father dragged away and clapped in the stocks for poaching.

Rural - She’s not unlike droves of other young women who come from the country to the city to seek their fortunes. She, too, has heard of the whoremongers that prey on such girls and their dreams, of the confidence men and tricksters and scoundrels. And as wholesome as the image she projects is, she’s innocent but not entirely naïve.

Extrovert - The girl talks a little too much. She inserts herself into conversations, rambles from one topic to another, laughs to fend off awkward pauses.

Soft of Heart - She’s careless with her kindness, and will lend her heart – and her tender regard – to any who want for gentleness and affection.

the road

The night that follows Vesper Bay makes her shiver with its silence. Out in the dust and the yawning canyons of that scabland, beneath a sky littered in stars, Clover realises that never before has she been so far from home and perhaps never again will she see the old road leading up to the farm. The old and busted mules tied to their wagons, anguish set to their frames as they rattle their way down towards Peddler's Bend. The dawn light streaming through the kitchen window, catching in her sister's hair. The tiredness in her mother's eyes. Her friends, unaccountable in their numbers. Deep within her, there’s a quiet ache for something lost, but it is small and it is distant as her companion sleeps soundly in the bedroll across from the crackling fire. On the road, he always sleeps soundly, and she thinks that he’s so used to running away from something that he’s only at ease when he is.

Now she no longer lives her life by the turn of the seasons and the limitless cycle of ripening and decay, but by the pulse and thrum of their footsteps, the jingling cadence of his chocobo’s tack. The seasons that define her life are reduced to two: the one that makes the road dry and raises dust to cling to them and their clothes and their hair, and one which turns the causeways into mires and bogs their boots in mud.

The firelight catches the edge of something silvery, the mirror’s wooden handle jutting out from the bundle of her things under the sprawl of her bedroll. She pries it out, resting the flat of it against her knee, blinking slowly at the pale and round-faced girl blinking back at her. She tugs at the fichu around her throat, and pinches her cheeks. Her mouth hangs low and sulky.

The mirror was Ja’rhem’s gift.

memory

Softness. This one is all smile without the teeth, ivory cheek and glittering eye. She treads softly, like straw falling from a loft. She smells of dry herbs and red clay.

In the ripe fields of La Noscea, even poverty is blessed, the priests say. They know it better than the lowfolk of the country to whom the rolling golden fields are no pastoral paradise, but instead a fickle mistress that feeds them well one year, and starves them the next when the potatoes rot in the loam before they grow thumb-sized. The tithes are paid in sacks of grain, or if that fails, good livestock; the collectors care not if their bellies growl and their children watch on, hungry-eyed, as their milking cow is tethered to the official’s cart, and on Bessie treads down the dirt track, her dappled rump vanishing past the hilly horizon. They know there’ll be no milk now. For supper, it’s a feast of turnips. The turnips never fail.

A child is born and they name her Clover, and like the weed that grows happily upon the field against calamity and drought, even if the rich grass dies out, she’s bright and green and indefatigable. At eleven she’s sent off to a neighbouring farm, to the small relief of her younger siblings whose share in turnips duly increase.

The girl is satisfied with her lot: a little straw cot, breakfast at sunup, dinner at noon, and sometimes even a supper of soft goat’s cheese and dark bread. Her broad peasant’s face is freckled by sun and smiling as she milks cows, listens to the tales and stories shared by the labourers around the fire at dusk, bunks down happily every night in her straw cot and pulls a blanket over her and falls asleep. She dreams of places across the sea.

Soon the wide pastures grow too narrow for her, as she sups nightly on storyteller’s tales, and now that the hunger in her belly is sated daily, and she wants not for bread or ale, it’s the hunger in her heart that pangs her. Her world is enclosed by the row of beeches in the north, the row of windmills in the west and the tangled hedgerows in the south. Hankering for something unknown, she stands upon the cliffs and looks east, watches through the haze a far-off sloop cutting a path through the shiny sea. The foreman barks at her; the barleycorn won’t sow itself.

At twenty, with her snub nose, her wide-set eyes and mousy hair, she’s no girl of delicate charm, but hale and robust, her young limbs shaped with vigour, and her farm-maid’s hands are rough and red at the knuckles. Her eyes are bright and brown and attentive.

And she never tires.

......